Before I get to the lobsters, it helps to explain how intellectual property actually gets optioned in Hollywood, because it is rarely the way people think it does.

Most projects do not begin with a finished screenplay or a formal pitch. They begin with something smaller and less dignified. A magazine article. A long essay. A podcast episode. A story someone forwards with the note, “This feels like a movie.”

The option itself is not a commitment to make anything. It is a placeholder. A small, strategic payment that says, “Let us be the ones who get to figure this out.” It buys time. It buys exclusivity. Mostly, it buys the right to imagine out loud without competition.

Some of the most familiar films and series started this way. A nonfiction article that lingered longer than expected. A piece of journalism that felt oddly character driven. A story that was not about plot so much as tone, point of view, or access to a specific kind of human behavior.

This is how Hollywood convinces itself it is being original.

Which brings me to lobsters.

Last month, a news story circulated about a shipment of live lobsters on its way to Costco being stolen, valued somewhere around four hundred thousand dollars. The article framed the theft as part of a growing national problem. Cargo theft is apparently organized, scalable, and lucrative.

I understand why this should alarm me.

Instead, I started imagining how I would see it go down.

This is usually where I get into trouble.

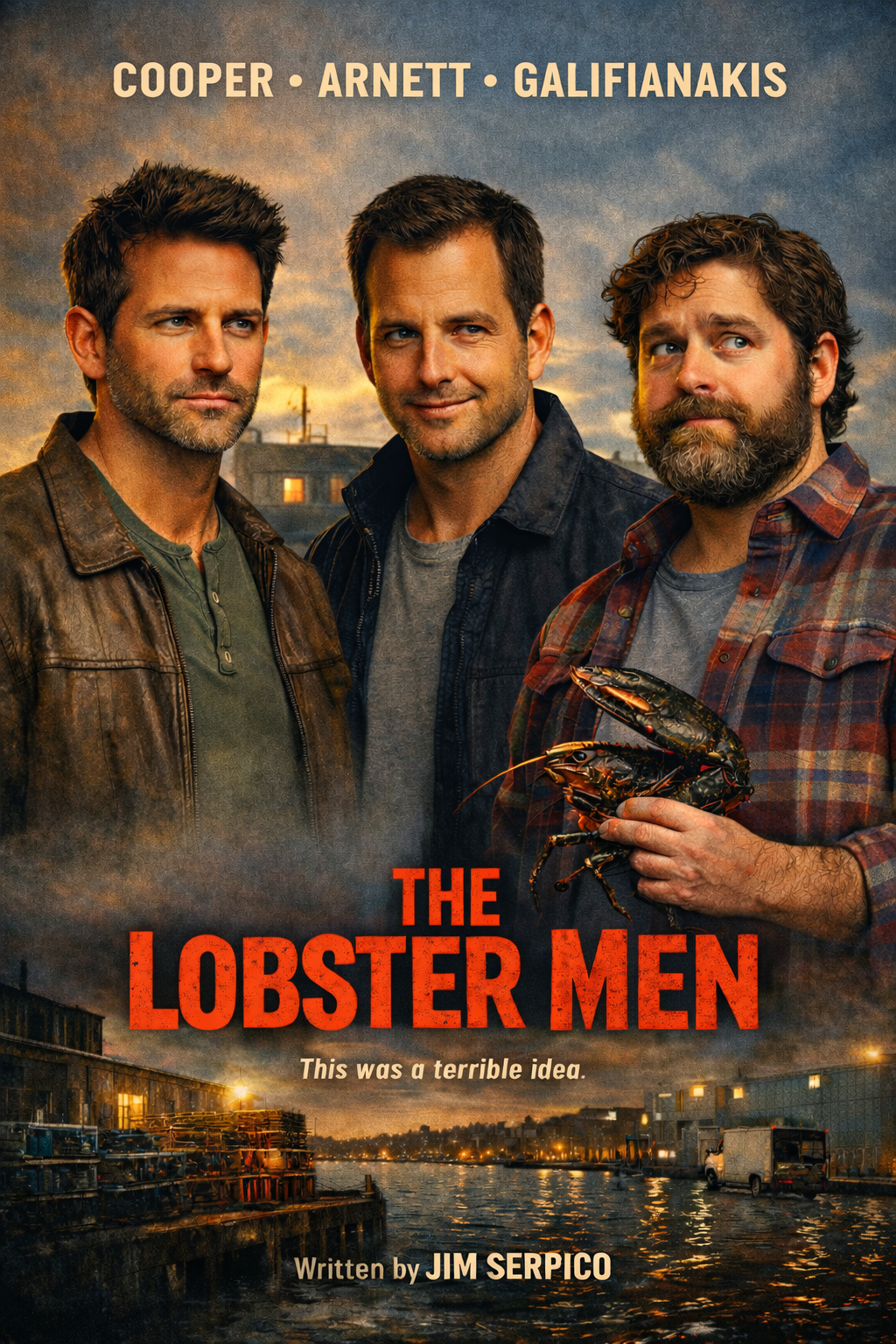

I did not imagine fictional criminals. I imagined actors. Bradley Cooper. Will Arnett. Zach Galifianakis. Not playing characters exactly, but existing as themselves inside the situation. Their public personas. Their rhythms. Their tells.

This is the first place the essay could stop and should not.

Why these three. Why now. Why crime, specifically seafood crime, as a container for thinking about middle age.

I suspect it has something to do with competence.

Here is a thing I have noticed about men in their forties.

We no longer fantasize about becoming something new. We fantasize about being useful again. Not morally useful. Practically useful. We want to matter in ways that can be measured.

This may be why crime stories age so well with us. They are not about chaos. They are about systems. Someone notices when you show up. Someone notices when you fail. Someone needs what you can do.

I cast Bradley Cooper first, which probably says something uncomfortable about my own relationship with control.

In my head, Bradley Cooper is single. This is not a romantic condition. It is an architectural one.

He owns jackets that imply a former life of motion. He eats dinner standing up because it is efficient, not because it is lonely. He has been out of prison the longest, which means he has had the most time to discover that being rehabilitated and being needed are not the same thing.

I do not think he misses prison. I think he misses clarity.

That is different.

Will Arnett arrives married.

Marriage, in this imagined version, does not make him safer. It makes him riskier. He understands consequences now. He understands how much there is to lose. This knowledge does not stop him. It simply makes him more articulate about why he should not be doing what he is about to do.

He tells his wife he is meeting old friends for lunch.

This is technically true, which is how most problems start.

Zach Galifianakis is the funny one. This feels obvious, which is why I distrust it.

Humor is often mistaken for chaos. In reality, it is control. It lets you redirect attention. It lets you hide timing. It lets you decide when the room is looking at you and when it is not.

In my version, Zach is also gay. This is not the reveal of the story. It is simply information that has been stored for a long time because storage felt safer than exposure.

Prison was not a place for honesty of that kind. Life afterward did not rush to correct that.

Zach is seeing someone.

Denis is a bookkeeper for the largest lobster exporter in Maine. Denis alphabetizes his spices. Denis believes rules exist because someone needs them. Denis does not know Zach went to prison. He does not know Zach is capable of anything particularly nefarious.

Denis believes Zach is charming, strange, and occasionally unavailable in a way that feels emotional, not logistical.

This is incorrect.

The butt dial is not funny when it happens.

It is late. Zach is half asleep. Denis is venting. Numbers are off. A shipment is delayed. Insurance language enters the room. Zach wakes up fully at exactly the wrong moment.

This is where a story would lean forward.

An essay leans back.

I start thinking instead about how intimacy works now. How much of modern closeness is accidental surveillance. How secrets arrive without being sought. How easily knowledge outruns consent.

Zach does not interrupt. He does not react. He listens.

When the call ends, nothing has happened yet.

That is the problem.

They meet in a diner north of Boston. This is the point where a movie would begin explaining itself.

Instead, they argue about coffee refills.

They split the check evenly. No one offers to cover it. No one insists. It is the behavior of men rehearsing fairness because they are about to abandon it.

Zach mentions lobsters.

He does not explain why.

Bradley understands anyway.

Will asks a question he already knows the answer to.

This is not a plan. It is recognition.

I will not describe the heist in detail because that would give it more respect than it deserves.

It works.

That is unsettling.

The warehouse behaves as if it has been waiting for them. No resistance. No alarms. No meaningful friction. The lobsters are alive, which turns out to matter later in ways no one anticipates.

Here is where the essay refuses to behave like a story.

The real problem is not selling the lobsters. It is living with them. They escape. They click. They turn an apartment into a place that feels watched.

Bradley’s home has never contained this much movement. Will checks his phone and places it face down. Zach receives a text from Denis that he does not answer.

Silence becomes the loudest thing in the room.

Selling lobsters turns out to be social.

Restaurants ask questions that feel personal. A distributor laughs and then stops responding. A church fundraiser ends early. An elderly woman says, “This is not in the bulletin,” which feels like a judgment that applies broadly.

Zach tells a chef he is gay because the sentence arrives before fear does. Nothing bad happens. Something internal rearranges itself.

Will lies to his wife again. The lie is smoother this time.

Bradley realizes that being needed for a crime feels dangerously close to being loved, which is how he knows it is wrong.

Denis almost finds out the wrong way.

He says calmly, “You disappear when things matter.”

This is worse than accusation.

Zach tells him everything except the prison part. Denis listens. Denis says Zach could have asked him to stop talking about work.

This devastates Zach for reasons he will understand later.

They release the lobsters at dawn.

A decorative fountain. Shallow water. No symbolism that survives scrutiny. The lobsters leave. The men remain.

Nothing resolves cleanly.

It is worth noting, mostly because pretending otherwise would feel coy, that this story would adapt cleanly to film. Three men. One absurd crime. Emotional stakes that have nothing to do with money. It is exactly the kind of project executives say they want when they talk about being tired of franchises and reboots, right up until the moment they have to actually choose one. For the record, it is available for option.

I do not think this is a story about a lobster heist.

I think it is about men mistaking relevance for risk.

Bradley learns that purpose does not come from being needed in the wrong way.

Will learns that honesty delayed is still dishonesty.

Zach learns that secrecy is not safety. It is just a quieter prison.

The lobsters survive. The diner stays open. Somewhere in Maine, an inventory spreadsheet will never quite reconcile.

I am left thinking that the most dangerous fantasy men carry into middle age is not the idea of one last job.

It is the belief that the only version of ourselves worth imagining is the one that already knows how to disappear.

If this is your kind of thing, I post essays like this every Monday morning. If you or someone you know would want them dropped into yours, you can sign up here.

Sign Up